The prevalence of neurodegenerative diseases (the so-called “dementias”),

especially Alzheimer’s disease (AD), is rapidly growing and the number of affected

people is estimated to double by 2050.

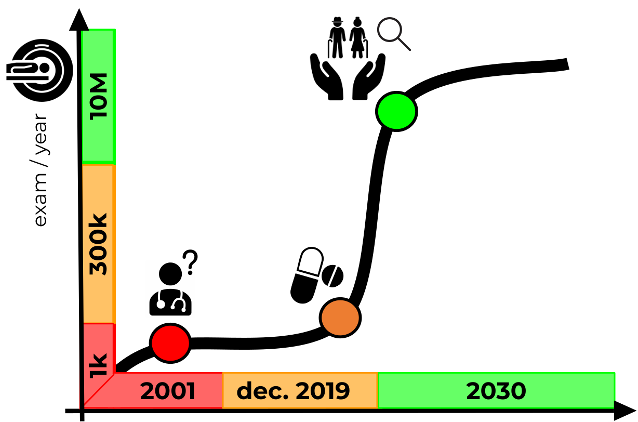

To date, the diagnosis of AD is done when clinical symptoms occur, that is, in a very

advanced stage of the disease. However, there is an abundance of confounding

factors (such as depression or lack of sleep) and symptoms of concomitant diseases (for example, the various forms of Parkinsonism or Levy’s body dementia) that make this assessment difficult.

It’s known that structural brain imaging (MRI) or even more functional (PET) brain imaging techniques can bring useful information for the prediction of the onset of symptoms (the “conversion to disease”) and the anticipation of diagnosis in a purely asymptomatic stage of the pathology.

An instrument such as PET with the tracer for amyloidosis (amyloid PET), although difficult to interpret, is the only non-invasive method capable of visualizing the accumulation of beta-amyloid protein in cortical tissue, considered as one of the first events in the degenerative process of the brain, making the diagnosis of Alzheimer’s disease even several tens of years in advance.

These images are assessed only qualitatively through a visual inspection and, due to the difficult interpretation, their use in the clinic is greatly reduced, despite the enormous advantages: this examination is often ignored for fear of errors.

It’s estimated that cases of misdiagnosis in hospital routines are around 30%, with the understandable inconvenience for patients, family members, and caregivers, as well as additional costs for the hospital system.

This percentage can be drastically reduced thanks to the systematic use of PET imaging and supporting the clinicians with an accurate quantitative analysis of this examination, as suggested by the most recent guidelines.